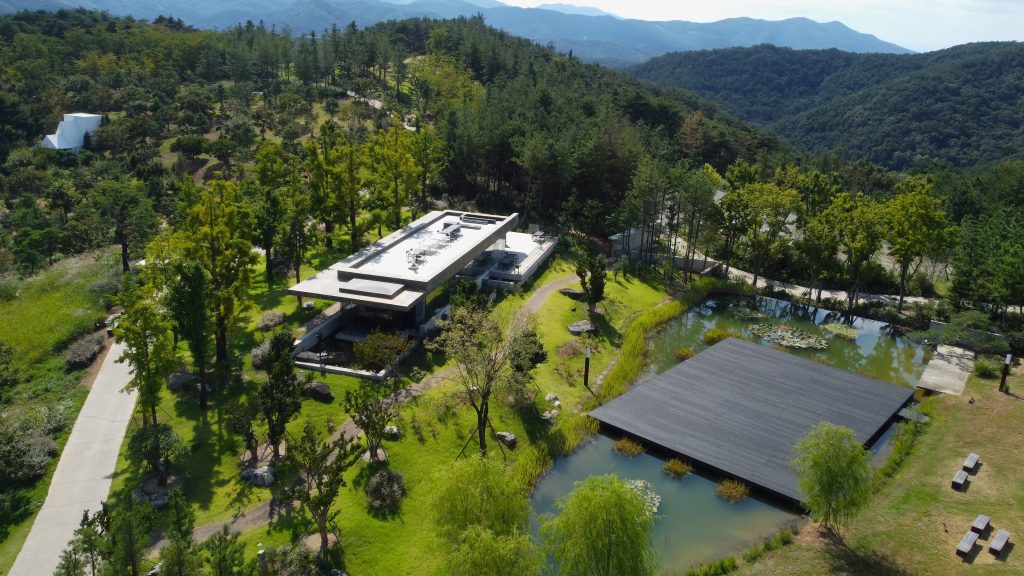

Notes: South Korea’s Sayuwon Arboretum and Architecture Park

What began as a preservation effort for 108 quince trees has transformed into a picturesque destination for contemplation

One year ago, I found myself standing among 108 quince trees on gently sloping land within Sayuwon, an arboretum and architecture park outside of Daegu, South Korea. I’d been anticipating the visit since my COOL HUNTING colleagues Josh Rubin and Evan Orensten posted a series of breathtaking Instagram images in May of that year. As an architectural tourist and sculpture park enthusiast—who has visited and written about Storm King, Tippet Rise, and Chateau La Coste—I became transfixed with the idea of finding my way to Sayuwon. Then Frieze Seoul, as well as an opportunity to stay with the culinary figure and monk Jeong Kwan, opened the door. In Sayuwon, after a lengthy drive from Seoul, surrounded by the quince trees, I paused and asked myself, “is this the most beautiful place I’ve ever been?” The answer is likely yes.

More than a garden for 108 quince trees, Sayuwon is a lush 330,000-square-meter arboretum and architecture park that’s set upon the Palgongsan Mountains. Visitors can start their journey at the top and trek down winding routes that vary in duration from one to four hours. Stunning vistas, tranquil ponds, and architectural interventions—from Pritzker Architecture Prize-winning Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, South Korean architect Seung H-Sang, and more—offer moments for contemplation.

Jaesung Yoo, the chairman of Taechang Steel, began to develop Sayuwon 20 years ago—though it only opened to the public in 2021. “At first, it was just for the family,” his daughter, Ella Yoo, the chairwoman of Sayuwon, told me during my visit. “There was no intention to open it. When we first started construction, we did not have a masterplan. It was organic. It was spontaneous. My father says that if he had intended to make it a profit-driven project, it would have never happened according to his vision.”

Remarkably, it all began when Jaesung Yoo acquired four historic quince trees that were set to be exported to Japan. “When my father found out, he decided he would not let it happen,” Ella explained. “He said, whatever price, I will pay it. He bought them back. The youngest quince tree that he bought was 300 years old. The oldest was 657 years.” Jaesung Yoo acquired more and his act of preservation continued to grow.

As for the region—which, to many, may feel quite remote—Ella shared that her father spent years exploring South Korea to find the ideal location. He chose Gunwi-gun because the population of the province itself is diminishing yet nature is flourishing. “This is the epitome of South Korean mountains, rounded and tree-covered,” Ella said. “The main concept of Korean gardens is borrowed scenery. We borrowed the mountains. Sayuwon was landscaped to see the mountain in its most beautiful form—and within the property, you have the extended scenery beyond that no one owns but it is seen in the context of the land. It is everyone’s.”

“It was just open mountains,” she continued, “and we tried to preserve what already existed—but many of the trees and plants have been introduced.” In addition to the vegetation, Jaesung Yoo oversaw the introduction of the architectural marvels. “My father strongly believes that architecture should not present an obstacle to see nature,” Ella noted. “You must first see nature and then something architectural.”

Four primary architects contributed to the park. Jaesung Yoo invited Carlos Castanheira and Siza from abroad because he wanted to imbue an international intrigue into the destination. “The overarching concept is eastern but he wanted it to be friendly to all visitors,” Ella said. She has observed that there is a very clear stylistic different between the architects. “The western architecture, it’s visible,” she said. “The eastern is often invisible. It blends into the nature.”

Siza’s work ranges from the intimate, one-person chapel known as Naesim Nakwon to the looming, concrete masterpiece entitled Soyoheon. The latter is an art pavilion that Siza had originally designed as a spec project to house Picasso’s “Guernica” and “Pregnant Woman.” When it didn’t seem to have tangible traction in Europe, Jaesung Yoo told Siza that he could bring it to life at Sayuwon. Siza was intrigued as “Guernica” is a depiction of the brutalities of war—and the mountain upon which Sayuwon stretches was a battle site during the Korean War.

Perspective shifts inside of Soyoheon—in a way that’s almost impossible to grasp. Some areas conform to the scale of the human body, others sprawl outward and upward. In place of Picasso pieces, Siza set his own immense sculptural works in the low, natural light. Though Soyoheon lends itself to subterranean sensations, it is also oriented out toward a vista—though, not as obviously as the Sodae/Miradouro observation tower, which was conceived by Siza as a partner piece to Soyoheon. It rises more than 20 meters into the sky.

Through her tenure, Ella has introduced more purpose-driven places to the grounds, including two restaurants. She also transformed the site’s first-ever property, her father’s vacation home, known as Hyeonam, first into an intimate restaurant and then, last year, into a tea house. Hyeonam (pictured in the hero image of this story) provides a panoramic view of the surrounding mountains. Here, alongside my colleague Julie Wolfson, I sat for a cup of quince tea that was produced on site at Sayuwon.

“I want you to think of Sayuwon when you are lonely or having a hard time,” a guide said just prior to our departure. And often I do. I think of our small tea ceremony in Hyeonam, overlooking uninterrupted forest. I think of the tiered Pungseol Gicheonyeon garden and its 108 quince trees. I think of how far Sayuwon feels from my home in New York City. And, for a year, I’ve thought about how I need to share my love of Sayuwon so that others can find there way to its splendors.

What are your thoughts?