Performance Art Biennial Performa Turns 20

An artist party, featuring a Performa Archives costumes installation designed by Charlap Hyman & Herrero, ushers in a milestone anniversary for the pioneering organization

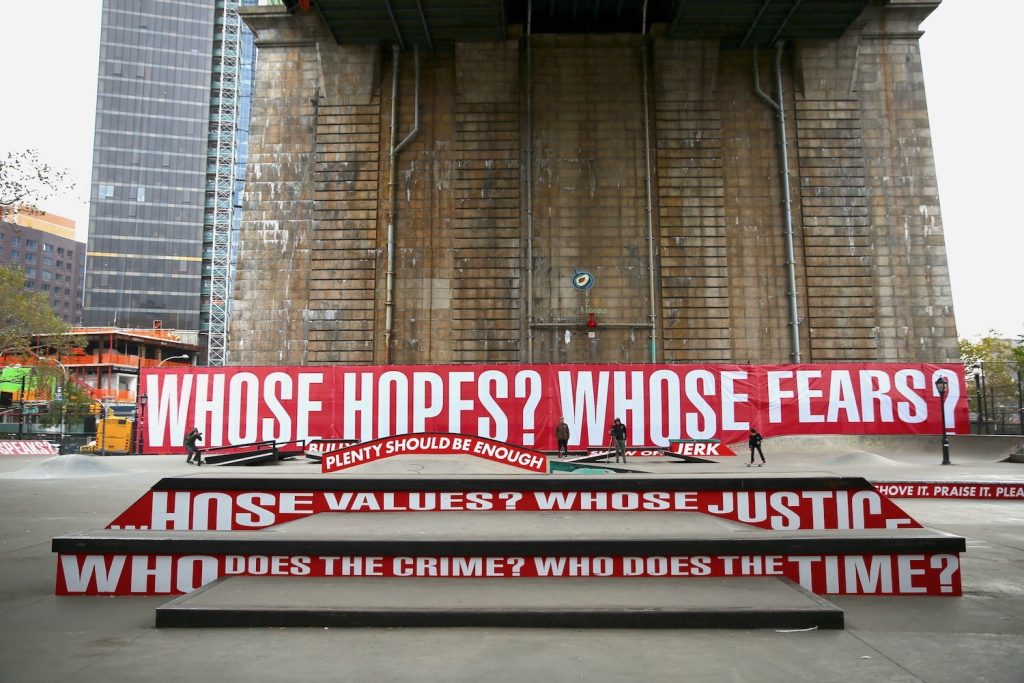

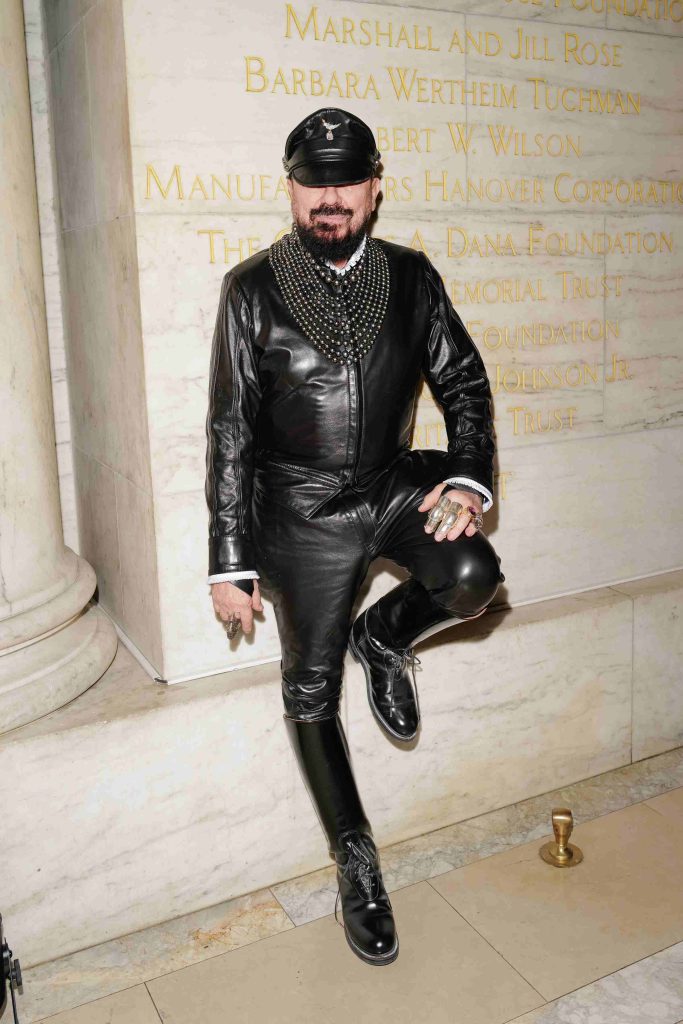

For the last twenty years, as the founding director and chief curator of Performa, RoseLee Goldberg has asked the art establishment and the art curious to keep performance top of mind and to consider its role in the historic development of other art forms. As a commissioning biennial, Performa has worked with numerous artists—many of the world’s most famous—to develop and premiere hundreds of performance art works within dozens of unexpected locations across New York City. This week, the organization celebrates its 20th anniversary with an artist party accompanied by a costume installation designed by Charlap Hyman & Herrero that features works from the Performa Archive—including pieces Marcel Dzama and Mike Kelley. It’s a theatrical exclamation point to the second decade of Performa’s necessary work.

Goldberg attributes her commitment to performance art to her upbringing in Durban, South Africa. “There wasn’t suddenly art and life,” she tells COOL HUNTING. “Art was all around. It wasn’t something that you just stopped at and said ‘oh look here is painting and sculpture.'” Goldberg pursued dance, as well as a fine arts degree—the two constantly vying for her attention. While studying at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, she saw an Oskar Schlemmer Bauhaus exhibition. “The Bauhaus was the first institution that set out to bring all different mediums together,” Goldberg recalls, “as well as the first to have a performance department.”

When Goldberg accepter her first job, as director of London’s Royal College of Art Gallery, she applied her Bauhaus learnings. “I presented the idea of the gallery as something that could integrate all the different departments of the graduate school,” she says. This led, in many ways, to a unification of the departments, as well as an immersion into diverse explorations of space and time—from the sound work of Brian Eno to performance art with Marina Abramovic.

In 1979, Goldberg shifted perceptions in the art world (and beyond) when Thames & Hudson published her book Performance Art. The seminole work, which has been in print for 45 years and translated into several languages, was the first chronicle of the history of performance art, with an emphasis on time periods linked to explosive ideas and exciting collaborations. Goldberg wove the history of performance art into that of broader art history in an informative, inspiring and accessible way.

Founding Performa in 2004 became a way to overcome the obstacles still present in the potential for widespread acceptance of performance art. “When I started Performa it was to stay ‘I am going to make this clearer on a much bigger scale.’ I felt like up until that point performance art had been presented as a sideshow,” she says. Performa has been successful as getting both individuals and art institutions to recognize that performance art has been integral to the history of art and culture—and at expressing how performance is capable of shifting ideas.

In addition to offering performance art a larger platform outside of the museum framework, Goldberg had two other goals. “I wanted to create a community around artists,” she says. “When I started it in 2004, the art world was—and still is—dominated by conversations around money and branding. The artists were at the bottom of the line. Today, the conversation often isn’t about the artists. They aren’t writing the manifestos or running the show. I want to bring the attention back to the artists.”

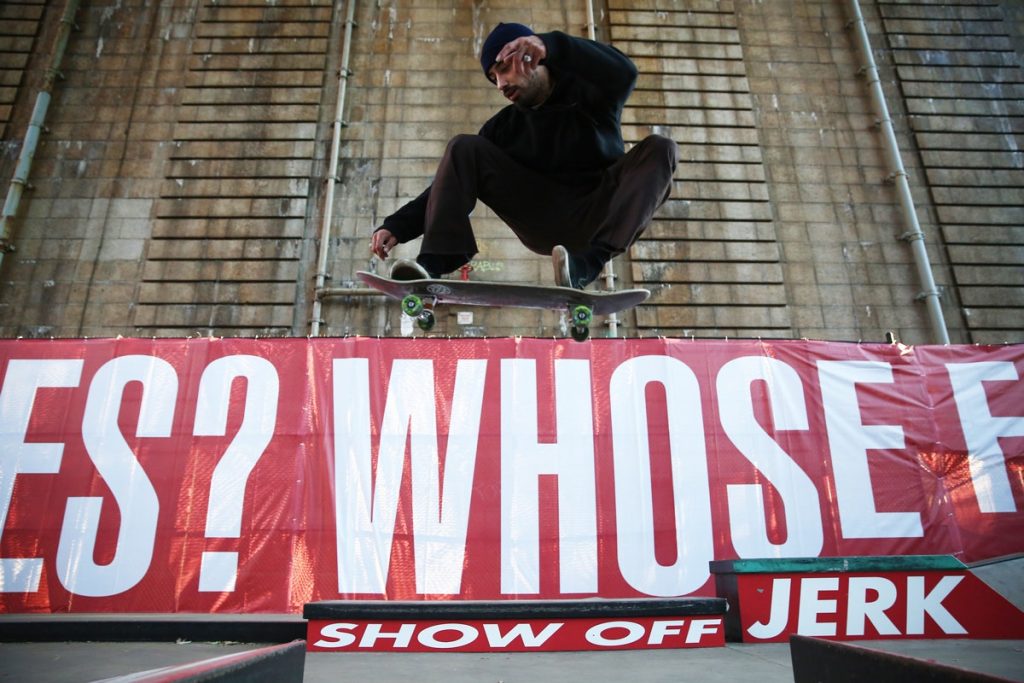

Further, Goldberg wanted to be able to commission works never before seen. “I had gone to performances three nights a week, everywhere around the world, for years,” she says. “I needed to see things that were moving to the next level—that were not just a brilliant idea, but that were executed without limits.” Underscoring this was a vision to approach visual artists whose work Goldberg felt could translate to performance art and asked them, “what if you went live? What would you do?”

Performa prefers a collaborative position with their artists. “It’s not just, ‘here’s a commission. See you in six months. Here’s your date. Here’s your funds,'” she says. “We start from zero. It’s not like I’ve seen something in Paris and we bring it to New York. We are not presenters. We are commissioners.” Goldberg says she’s always surprised and exhilarated by what the artist produces.

Through the success of Performa, Goldberg has observed that more traditional art institutions now recognize that performance art is a great way to interface with their audience. “It brings the audience in,” she says. “They feel much more connected to each other as a group and to the work. There’s a sense of learning from it. Whereas if you put someone before something more abstract, they might say, ‘I didn’t study art.’ They might not know what to say. There’s a much more visceral response for people outside of art history. They see it. They feel it.”

Goldberg sees performance art as the medium of the 21st century—and she can clearly identify the role that Performa will continue to play. “This is a place where you will discover its history, and you’ll learn that its quite remarkable, whether you’re coming in as an economist or as a dancer or a filmmaker,” she says. “You will be excited about what this says about society and how we think about live performance.”

As for her thoughts on galas, Goldberg explains that while they are necessary to arts organizations like Performa for operational funding, she knew from the beginning that theirs needed to be different. In fact, their first-ever gala was a reference a Laurie Anderson piece from the ’70s. Everyone was asked to wear white and films were projected. In essence, the attendees were the screens for the films. For this year’s gala, Performa is looking toward its own history and extensive archives with intention. This is how Dzama came to be involved.

“I did a piece with Performa last year,” he tells COOL HUNTING, referencing “To live on the Moon.” “It was a film and musical performance about Federico Garcia Lorca. He had written a screenplay. The Lorca Foundation had given it to me. They wanted me to perform it but their funding fell through. Performa made it possible.” Some of the Dzama costumes at the gala were used by characters in the Lorca film.

When asked what has changed with Performa over the last two decades, Goldberg says not much. “We are as fiercely determined as ever to gather together the brilliant, creative souls of this city to show how art changes us,” she explains. “And, we are always moving forward. I always think you’re only as good as the next one.” Next year, Performa will place their groundbreaking performance art commissions throughout New York City for their 2025 biennial, running 1-23 November.

What are your thoughts?