Fondation Louis Vuitton’s Mark Rothko Retrospective

A profound exploration of an artist’s journey of transformation

With Mark Rothko at Fondation Louis Vuitton, viewers are treated to a reverie of color, emotion and history as the artist’s vibrant canvases take center stage. This major retrospective, the first of its kind in France since 1999, offers a deep dive into the life and oeuvre of this pivotal figure in abstract expressionism—and features a staggering 115 works drawn from around the world. Born as Marcus Rotkovich, Rothko—a Latvian-born Jewish immigrant—fled to America to escape persecution, landing in New York City, a place that would serve as the backdrop of his formative years as an artist. The pulse and rhythm of the city, from the bustling subways to the towering skyscrapers, informed his early works. These intimate cityscapes capture the duality of Rothko’s existence: an outsider looking in, grappling with the enormity of the metropolis and his place within it.

From his early beginnings until the pivotal year of 1940, Rothko developed a figurative body of work that was deeply rooted in the exploration of the human subject. His canvases depicted anonymous figures, ranging from nudes to portraits and urban scenes. During this period, Rothko pushed the boundaries of representation to their limits, constantly evolving and simplifying forms. Rothko’s paintings embraced greater fluidity of space and incorporated vegetal and animal forms. Plants, birds, totems and “organisms” drifted through subaquatic spaces, subdivided into differentiated zones. The titles of his works, which would later disappear, provided insights into the content’s evolution toward clarity, aiming to eliminate any obstacles between the artist, the idea and the observer.

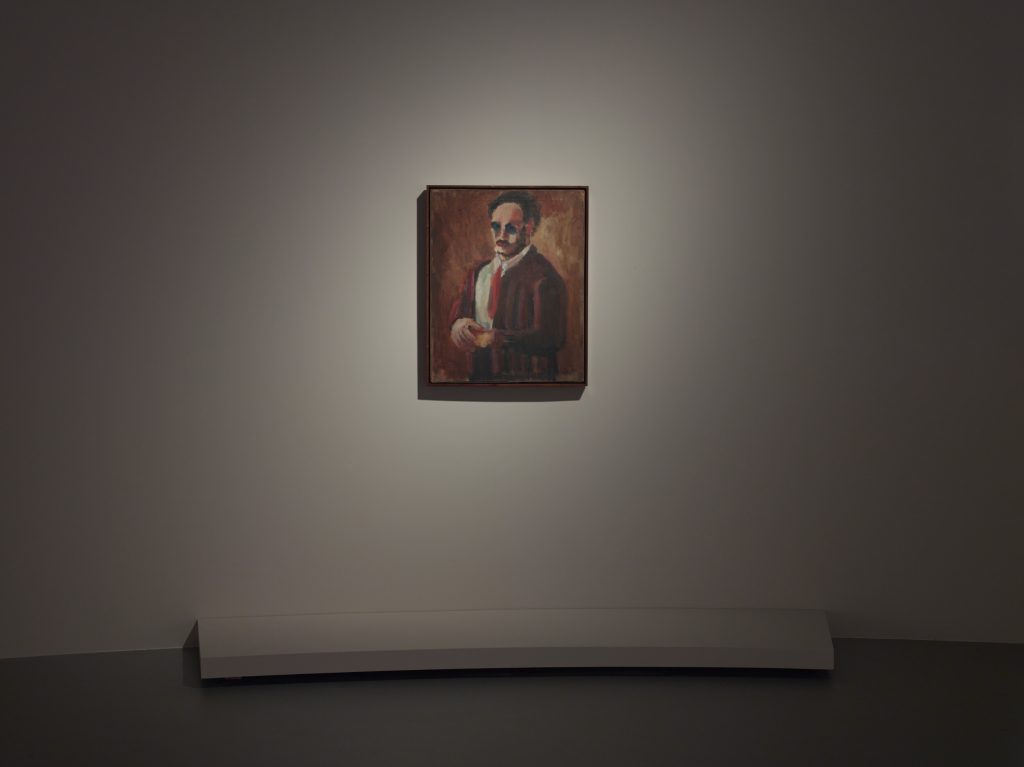

The exhibition commences in Gallery 1, featuring Rothko’s only self-portrait, which dates from 1936. This imposing figure exudes gravitas, with the artist’s gaze concealed behind dark glasses. The self-portrait captures an air of impenetrability, as if Rothko is intensely focused on an inner vision that reveals nothing of the man or the painter himself.

Influenced by prominent painters such as Milton Avery and Henri Matisse, Rothko’s expressionist brushwork evolved, shaping the early stages of his artistic career. However, as the 1930s drew to a close, Rothko made a significant shift in his artistic direction. He abandoned figuration, feeling that he had been unable to faithfully represent the human figure without distorting its essence. This momentous decision led him to a period of introspection, during which he temporarily ceased painting and delved into the realm of theoretical writing on art, culminating in his posthumous work titled The Artist’s Reality.

The 1940s brought with them a tumultuous global context, including the horrors of World War II. In response to these challenging times, Rothko, alongside his friends Adolph Gottlieb and Barnett Newman, embarked on a quest to invent what they referred to as a “contemporary myth.” Drawing inspiration from ancient mythologies and totemic forms, Rothko aimed to formulate a universal artistic language as a response to the prevailing barbarism.

Rothko’s artistic vocabulary began to incorporate biomorphic elements during this period, thanks in part to his exposure to Surrealism. American artists had become familiar with Surrealism since the 1936 exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism” at MoMA, and the arrival of leading Surrealist representatives in New York City due to their exile. Peggy Guggenheim, a notable figure in the art world, promoted this aesthetic in her gallery, “Art of This Century,” where Rothko first exhibited his work in 1944.

By the late 1940s, Rothko transitioned into a more abstract phase with his creation of the “Multiforms.” While the initial compositions retained a dense and organic quality, starting in 1948, they began to feature a more defined structure, thinner layers of paint and larger vertical formats. As early as 1949, Rothko introduced a distinctive composition characterized by superimposed rectangles and a luminous, translucent color palette. He abandoned descriptive titles for his works, opting instead to number them.

In the early 1950s, Rothko’s signature style began to emerge. His paintings became instantly recognizable, featuring two or three rectangular, colored shapes superimposed upon each other. This interplay of shapes allowed for an infinite range of tones and values, creating the characteristic vibration that is so closely associated with Rothko’s work. The atmospheric quality of his brushwork bestowed upon the canvas a mysterious and almost magical quality. Rothko himself stated that behind the color, he was in search of light. During this period, the canvases continued to grow in size, enveloping the viewer in their immersive presence.

octobre 2023 au 2 avril 2024 à la Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko – Adagp, Paris, 2023

At the heart of this exhibition are Rothko’s abstract works from his renowned “Classic” period, which began in the late 1940s. This period is marked by Rothko’s emergence as a unique colorist, whose mastery of color reaches a radiant and mysterious brilliance. Galleries 4 through 11 showcase approximately seventy works from this period, including two exceptional ensembles from the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, and the Seagram Murals from the Tate Modern.

The years from 1945 to 1949 marked a decisive shift toward abstraction in Rothko’s art. His paintings broke free from traditional easels and were classified as “Multiforms.” Undefined chromatic fields were populated with biomorphic elements, with thin layers of color replacing traditional drawing. These elements floated in transparent spaces, inviting viewers to explore their enigmatic depths.

In the early 1950s, Rothko’s art reached its zenith with the creation of what would become his iconic “Classic” works. These paintings featured bright high-keyed colors in a falsely monochromatic or highly contrasted chromatic field. Rectangular shapes of radiant color with undefined edges were layered upon one another, creating a binary or ternary rhythm. Through multiple translucent strata, an infinite range of tones, values, chords and dissonances unfolded, culminating in a flamboyant chromatic apogee. The atmospheric brushwork infused the entire canvas with a mysterious and emotional quality. Rothko’s art was an exploration of light, far more than just color.

The scale of his paintings continued to grow, enveloping viewers and immersing them in an intimate experience. Rothko’s desire was to create a sense of intimacy through large pictures, where the viewer’s engagement with the artwork was immediate and deeply personal.

This desire was in part inspired by his fascination with Henri Matisse’s “The Red Studio,” which he had encountered at MoMA. In this painting, a space filled with objects was unified by monochrome color, flattening the space along the picture plane to the extent that the viewer became one with the color itself. Rothko sought a similar effect in his mid-1950s works, expressing his wish to present his paintings as a distinct ensemble within a space saturated with specific colors. This immersive experience aimed to absorb the viewer, offering a sense of contentment.

Rothko was cautious about his works being perceived as decorative and insisted on emphasizing the notion of light. Yet he acknowledged the sensual and emotional power of his art, recognizing the relationship of pleasure and emotion it forged with its audience. His works were simultaneously serene and intense, and Rothko himself acknowledged the inherent violence concealed within every inch of their surface. The captivating allure of Rothko’s art lies in its ability to elicit profound emotions and reflections. This depth is particularly evident in the Seagram Murals. These works, marked by a darker range of colors, exude a meditative interiority.

Originally commissioned for a dining room designed by Philip Johnson in a Mies van der Rohe building, Rothko eventually abandoned the commission. His desire was to recapture the essence of the space/enclosure he had experienced at the Laurentian Library in Florence. The Seagram Murals, presented here in their entirety as the “Rothko Room” at the Tate, convey a sense of transcendence, inviting viewers to lose themselves in their contemplative depths.

These works feature rectangles that have evolved into more open signs, some interpreting them as portals or thresholds. Color takes on a newfound gravity in this series, with reds and maroons prevailing, albeit with a muted intensity. The relationship with architecture becomes more pronounced, adding a contemplative dimension to the viewer’s experience.

The journey through Rothko’s artistic evolution culminates in Gallery 10 with the Black and Gray canvases including the monumental work “Cathedral” (1969-70), prominently displayed alongside sculptures by Alberto Giacometti evoking a more austere atmosphere. Giacometti, like Rothko, grappled with constant doubt and a shared sense of humanism, and their works engage in a profound dialogue within the gallery space. Rothko had envisioned presenting these works alongside “The Walking Man” as part of a commission for the new UNESCO building in Paris. These paintings, characterized by contrasting zones of black, brown and blue-gray tones, separated by a continuous line, initially met with incomprehension. Today, interpretations of these late works have evolved beyond mere biographical references to the painter’s health or mental state. In resonance with Giacometti’s sculptures, these canvases convey a density, solemnity and tension that rekindles Rothko’s poignant exploration of emotion in a new form. Contemporary artists have expressed a preference for these late works, praising their aesthetic advancement and their departure from the conventions of abstract expressionism.

Gallery 11, adjacent to Gallery 10, showcases works from the same period as Rothko’s “Classic” paintings. These oil and acrylic canvases from 1967 to 1970 are a testament to Rothko’s artistic vision. Their bright high-keyed colors dispel any notion that Rothko’s colors merely reflect his psychological state. Instead, they invite viewers to immerse themselves in the radiant and mysterious brilliance of color, transcending the boundaries of emotions and perceptions. In this retrospective, one gets more than just a glimpse of Rothko’s artworks, it is a profound exploration of an artist’s journey of transformation. It transcends time, borders, and language, inviting us to contemplate the depths of the human spirit through the vibrant and emotive strokes of his brush. Rothko’s legacy endures, reminding us of the power of art to engage our emotions and spark introspection.

What are your thoughts?