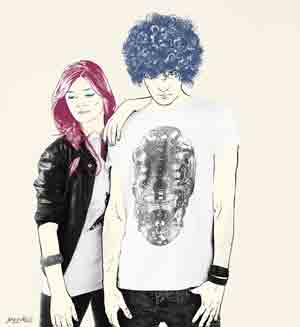

Interview: Italian Fashion Designer Jezabelle Cormio

The emerging talent speaks about alternative style, gender roles and what it means to make truthful design

For decades, novelties in Italian fashion were rare when it came to new brands and designers. This has changed rapidly in recent years, as evidenced by the increasingly frequent international awards attributed to the new generation of Italian designers. Among these, Cormio is undoubtedly one of the most exciting.

Jezabelle Cormio, a designer of Italian American origin based in Milan, founded the brand after studying at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium, under famed director Walter Van Beirendonck. Her brand was immediately characterized by an eccentric aesthetic vision, defiant of traditional gender roles, that embraced kitsch.

Recently, Cormio was one of the participants in Forces of Fashion, an international event curated by Vogue in Rome. There, we met her to discuss fashion, family, tailoring and what it means to be a designer today in Italy.

Let’s start with your fashion education. You choose Antwerp, where creativity is seen as more important than industry.

In Antwerp, fashion design culture is based on personal DNA. The stakes are high—to find out who you are and then build this little brand based on yourself through the years. Students are not asked to think about the commercial side or propose things that they would see, let’s say, in a Versace show. No one’s asking anybody to think, “What would I do if I worked at Dolce & Gabbana?” No one cares.

How were you able to combine this northern European drive toward self-expression with a more commercially oriented Italian side?

One thing is, I don’t really see my work as very Italian. I think many people are surprised sometimes when they find out I’m Italian. I’m not trying to look Italian, but I am also Italian; I can’t choose. One thing that I find really fun is to think about Italy from outside and inside at the same time. Because I’m half American and half Italian, I always enjoy critical thinking by looking at the other country from the outside.

Your sources of inspiration—like Tyrol or soccer—are unusual for the fashion world. What makes those references interesting to you? Is it a way to distance yourself from tradition?

When I went to South Tyrol for the first time, I was in my mid-twenties. All the souvenir stores were filled with stuff I’ve seen my whole life, everywhere. I’ve seen traditional stuffed hearts in Puglia, pot holders in my aunt’s kitchen, Roman guys with Austrian coats, rich people’s weddings in Switzerland or Austria.

I think the Tyrolean aesthetic is appropriated by the Italian upper class to distance themselves from the Italian vulgar aesthetic that we can’t get rid of. There are codes; it’s pure, it’s clean. Also, the food, the water and the air are supposedly clean and pure there. And then, on the other hand, I also see that Germanic side that is very funny, like sausage, beer and sex jokes.

Is there anything from classic tailoring that influences your work?

I have a love-hate relationship with tailoring. Sometimes, it’s a cage; sometimes, elegance is a cage. It’s a little bit of an alibi for not having something else to say. I really like jerseys and denim now. And graphics and embroidery. I’m not saying that one day I won’t get a lot of satisfaction from tailoring, but there’s something so immediate, youthful and communicative about these other things.

The first time we saw something from Cormio, we fell in love with your embroidery. It recalled some very intimate memories from youth. I’m sure that many others recognize something personal in your products. Do you think about that when you design?

I used to think about it a lot in the beginning, and then it started rolling freely. When I was a small child, my great-grandmother was the only person in the family tree who could make anything. She would knit us sweaters and they were my favorites. Sometimes, they had these fibers that we wouldn’t see in Italy because it was from my American great-grandmother. They had magical powers to me like you can’t lose it, it can’t break.

When I started making clothes a few years ago, I couldn’t imagine somebody taking something I made and throwing it away. So, I try as much as possible to create a bond between the person and the clothing. If it has an emotional response or this tactile aspect of embroidery, if you can tangibly understand it’s been handmade, I think people develop a stronger relationship. They don’t just look at it as something that was supposed to fix some bad mood two weeks ago.

We know you have a passion for eBay, Etsy, Vinted and others.

Yeah, it’s my part-time job to find useless things!

Tell us more about that.

It goes in phases because I need a lot of time. My latest obsession is subito.it because I find all the best things in the world. I love to scroll until I’m completely nauseous and my finger hurts. And then I find something, and I could drive to Naples to get it. I don’t care. I just moved into a new house. I went to Modena, put a wardrobe for my daughter on top of the car, and drove back home in the rain.

On eBay, I buy a lot of stuff. The good thing about eBay is that the platform has never really gotten up to date. It’s so uncomfortable to use that lazy people don’t use it. Stuff stays on eBay for longer. Whereas Vinted is so immediate that people are just constantly buying. And the shipping is pretty cheap. People buy really fast on Vinted, but eBay has remained the Amazon forest of online platforms.

In a recent interview, you said that in your vision for menswear, you wish that boyfriends could steal objects from their girlfriends.

That would be fun. It’s not gender neutral; it’s dress up. This is how I feel comfortable. It’s not if you’re a girl you wear a skirt, if you’re a boy you wear pants. It’s more like [finding] the safest area, and you can have fun outside it. There is a real fascination with stealing stuff from your boyfriend’s wardrobe or a woman appropriating a man’s wardrobe. But men don’t do it because they feel emasculated.

I noticed that in your photo shoots, there are a lot of women of all ages and many children, too. Why is this?

It has to do with the fact that I have a child. It was tough to reconcile having a family and not resigning from trying to feel young, dynamic, in touch with the world, and cool in a way.

But when I had the child, I didn’t have any references. I didn’t know anybody with kids; none of my friends had kids. I realized there was so much prejudice from my circle of people, the creative class or the new generation. People are very afraid of giving up everything that they have conquered to become bourgeois, bland parents. I found it very hard to reconcile those two things because I felt like I was being asked to abandon everything I was before and just hear, “Be on time at the kindergarten! Bring the fucking diapers! We don’t care that you have a company to run, fit in with the other moms!”

I thought there had to be more imagery about being young and having a child. I’m not even that young. I had a child at 30; nowadays, I’m considered a very young mother. I also thought one thing that was expected of me was to abandon all forms of sensuality or personal sexual identity.

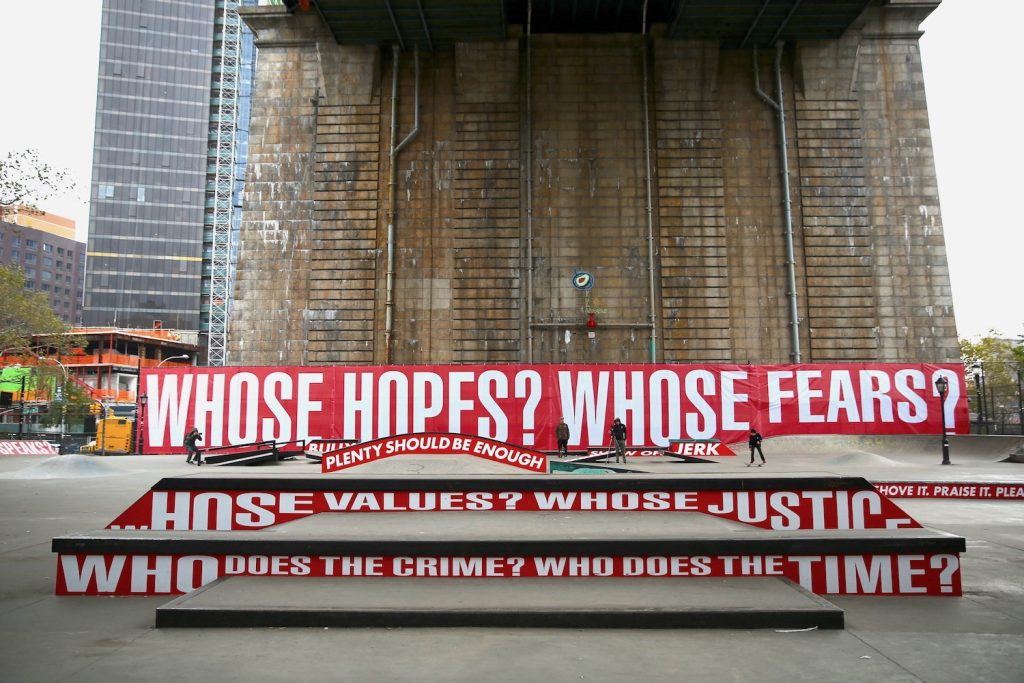

You are part of the new generation of Italian designers selected by Vogue for Fashion Panorama and now the Roman edition of Forces of Fashion. You all have your brands and are not creative directors in big companies. You all know each other, and some of you are close friends. Do you see yourselves as a group?

We know each other, and we are close. We get together when we have to discuss industry dynamics because we all get the same treatment, in a way. From a sociological point of view, we have our own brand because we don’t fit in with the other brands. And the other brands are so big that they take up all the space. I’m sure we were all lucky for some reason.

I’ve had this brand for four years, but I can say I’ve had it for 10 years in different forms. I started producing things under my name when I was still in university because of some lucky opportunity with Opening Ceremony. Then, I didn’t know how to push it forward for a while because I didn’t know anything: I didn’t know about showrooms or investors; it just looked very slow from the outside.

We also live in a society that hates young people right now. The fact that you might want to go and do something on your own seems like a survival tactic in a way.

Will you be able to change aesthetics? We ask that because the things you and your colleagues make are sometimes tricky to understand and they’re not highly commercial. It is brave.

Or naive. Could we change the aesthetics? Yes. The question is how fast and how much, what does it take. When I see the big maisons, some look identical for years. There’s nothing new, and it’s also not very specific to our time. And then there is also the fact that very big brands make everything that is trending right now. They don’t pick sides. They don’t just say, “We won’t do the baseball hat.” No, everybody does the baseball hat. It’s so smooth, but it’s also a little bit bland.

I think the opposite of that is probably a brand that doesn’t do everything and does a very specific, truthful design. On a tactile level, it feels a bit different because something that is not mass-produced has a taste; it really has a feeling.

What are your thoughts?